Whitewash

A Fresh Look at The Problem We All Live With

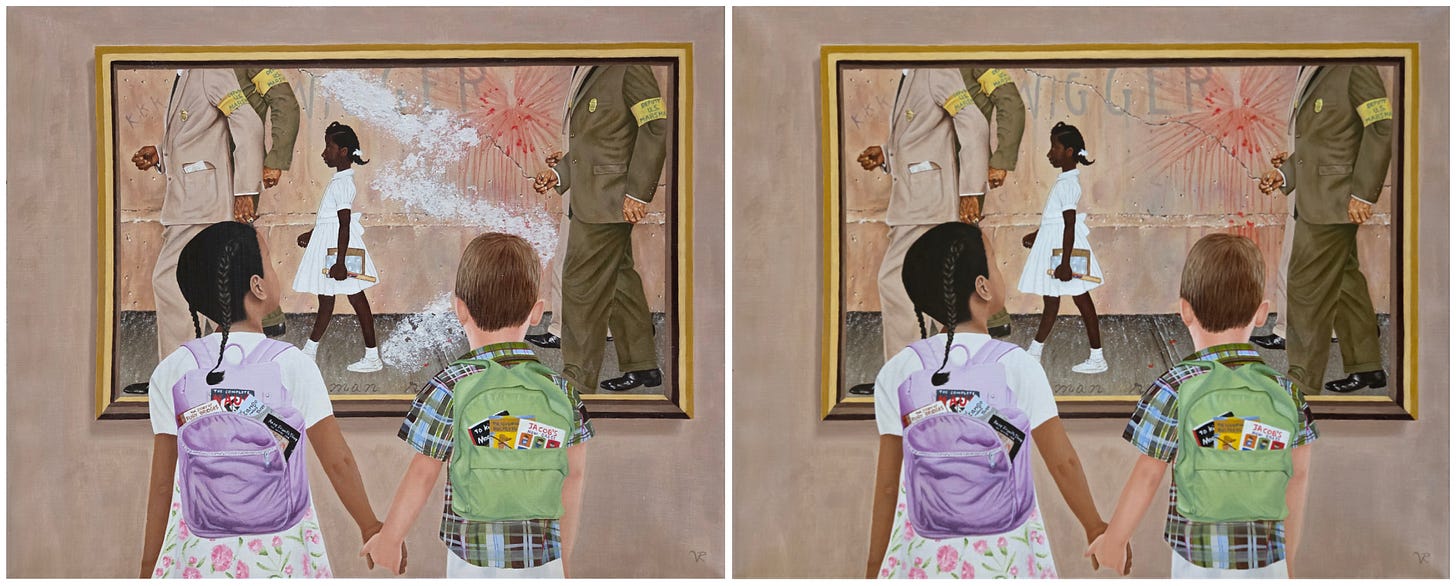

I've completed the painting I’ve been working on for some time, titled “Whitewash.” The term itself refers to the act of covering up or concealing unpleasant facts. It involves downplaying or ignoring scandals or negative issues to maintain a positive public image.

The painting is 24x30, oil on linen canvas, and includes a lot of symbolism relating to today’s politics, particularly within what is left of the conservative movement. And so, let’s dive into the historical aspects of the painting behind my painting.

This is my take on Norman Rockwell’s “The Problem We All Live With”, 1964. His painting depicts Ruby Bridges being escorted on her way to the William Frantz Elementary School, which was an all-white school during the New Orleans schools’ desegregation in 1960. Because of the threats of violence against 6-year-old Ruby, she is led by four deputy U.S. marshals to school. The painting is framed so that the marshal’s heads are cropped at the shoulders, making Ruby Bridges the only person who is fully visible in the painting, lending more of an impact on the circumstances. On the wall behind her is a racial slur and the letters “KKK”. A tomato is thrown against the wall, which has splattered and fallen onto their path. The white protestors are not visible as the viewer is looking at this scene from their point of view, as one of the protestors or as an onlooker.

Nostalgia Shattered

Up until this time, Rockwell centered on the themes of typical Americana. As an illustrator for the Saturday Evening Post, he created in the minds of white America the view and identity of life for the average person. It was only after he left the Post in 1963 that he was able to paint the changing world of the 1960s around him. Instead of painting the nostalgic white world that existed in the pages of the Post, he began to paint integration, poverty, and controversy. His assignments with Look magazine would be different.

In the civil rights era, Rockwell exposed the ugly truths in American society. He painted, “Murder in Mississippi”, which depicts the 1964 murders of civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, and was intended to illustrate an article written on the murders by civil rights attorney Charles Morgan Jr. Another painting, new “Kids in the Neighborhood” featured black children moving into a white neighborhood, highlighting the tensions of housing integration.

It was soon revealed through his art that the sentimental ideal of small-town America did not exist in reality. This was an era that was created through the eyes of racism and white supremacy, where black people did not exist. That ideal only existed in TV series and movies of that time, a time where anyone who was not white was pictured as servants, cooks, maids, or had menial tasks as gardeners or someone’s chauffeur. In real life, they had to obey white men, stay in their place, or be lynched.

When Rockwell painted “The Problem We All Live With”, it became one of the most iconic paintings of the civil rights era.

Becoming “Woke”

The editors of the Post were not interested in picturing “Black America”; they wanted the status quo to remain. Up until this time Rockwell painted mainly for the white community, possibly without realizing it. That wasn’t because he only had an interest in white Americana, it was only what the editors of the Post would allow. Rockwell had tried to paint African Americans into his paintings but at one point he had to remove a black person from his painting because the person wasn’t in a position of service. It seems the only acceptable position for the Saturday Evening Post for a person of color is one pictured in service to the white community.

All this changed in the upheaval of the 1960s. Rockwell’s Golden Rule was a call to conscience. This was a painting that depicts a diverse group of people from all walks of life and of all different races, religions and backgrounds, all gathered together as a portrait of humanity. The central idea emphasizes mutual respect, empathy and equality for all under the banner of “Do unto others…”. It appeared on the cover of the Post during a time when the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum with sit-ins, Freedom Rides, and public demands for desegregation and voting rights. It highlights racial harmony and a common humanity at a time when America was deeply divided along racial lines.

This social upheaval influenced Rockwell to begin to use his art more directly to comment on racial injustice. After leaving the Post, Rockwell went on to create even more direct Civil Rights themed works, like The Problem We All Live With. Six days after John F. Kennedy was elected on November 14, 1960, Ruby Bridges was the first Black child to desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana. The New York Times reported:

Some 150 white, mostly housewives and teenage youths, clustered along the sidewalks across from the William Franz School when pupils marched in at 8:40 am. One youth chanted “Two, Four, Six, Eight, we don’t want to segregate; eight, six, four, two, we don’t want a n*****.”

Forty minutes later, four deputy marshals arrived with a little Negro girl and her mother. They walked hurriedly up the steps and into the yellow brick building while onlookers jeered and shouted taunts.

The girl, dressed in a stiffly starched white dress with a ribbon in her hair, gripping her mother’s hand tightly and glancing apprehensively toward the crowd.

Here is a little girl being hurled racial slurs and hatred from the crowd. The insults were insulated and censured from the TV News screen but in the mind of Rockwell, it struck a cord and rang out loud. It rooted into the consciousness of Rockwell where it planted and grew for three years when it found it’s way to the surface. It was a turn in Rockwell’s career personally and one that could have had disastrous results with his reputation and legacy. With this painting, he has turned his back on white America and betrayed their values of supremacy.

The Problem We Still Live With

Everything about this painting grabs you and leaves you with a sense of violence and hate. From the starkness of Ruby as the centerpiece to the racial slur and the red splatter left behind on the wall with the tomato sliding down and landing on the path reminsent of blood - all leave visual evidence of the violent hatred she faced. Her youth and innocence amplify the cruelty of those who opposed desegregation, exposing the moral bankruptcy of segregationists.

The title itself — The Problem We All Live With — suggests that racism is not just a problem for Black Americans or civil rights activists, but a deep moral failing shared by the whole nation. It calls for collective responsibility and action.

The composition leaves you, the viewer with a sense of participation. You are standing and viewing the events as they unfold. You are the one that possibly hurled that tomoto. You many have been the one that screamed out racial slurs as she passed by you. You are the problem we all live with.

Rockwell, once considered merely a sentimental illustrator of American life, made a bold and unforgettable statement with this painting. It stripped away the myth of a wholesome, unified America and laid bare the realities of hate — but also the courage of a single child and the possibility of justice, even when it is slow and hard-won.

The Problem We All Live With continues to resonate because the problem - racism -still persists. While the circumstances and expressions of that racism may have evolved, the core issues of inequality, injustice, and moral responsibility remain. The painting serves both as a historical document and a moral mirror, asking each generation: What are we doing about the problem we all still live with?

Whitewash

I chose to reproduce this painting as it is still relevant, maybe even more so today. I wanted to add to the meaning of the painting and make people stop and think about where we are and the actions they take. I’ve added different elements to the racism that already exists in the painting.

In my composition, as in Rockwell’s, you are looking at the painting and its historical context. You once again are a part of the painting standing behind the children. But this painting has been spray painted, crossing out the racial slur above Ruby’s head and all the way to her feet. It begins and ends with her which tells us that she is still the focal point of the painting. But there is something different about this spray paint, which we will get to in a moment.

Two children, inter-racial children, are looking at the painting. They hold hands while the little girl looks up at Ruby in the painting and the little boy seems to be looking at either the spray paint at Ruby’s feet or possibly the smashed tomato on the path. Does he feel partly responsible for the past and does she recognize the significance of history that seems to be covered up. Are you standing behind them?

They both have backpacks containing books. Did they come from the library? Are they on a field trip? Take a closer look at the books. These are actual book titles that the conservatives have banned from schools. The books the little girl has are “The Story of Ruby Bridges”, “The Complete Maus”, “And Tango Makes Three”, and “Anne Frank’s Diary”. Each of these titles were banned for various reasons by conservative groups.

Suppression and Censorship

Ruby Bridges' book, Ruby Bridges Goes to School, and other biographies and stories about her experiences during desegregation have been targeted as "inappropriate" or that they make white children feel bad. Bridges herself has spoken out against these efforts, calling them an attempt to "cover up history". The Complete Maus, illustrated in the style of a comic book, is a story about the Holocaust and was banned due to “inappropriate language” and nudity. The nudity was the mice in the illustrations! Another illustrated book, Tango Makes Three had “homosexual overtones”. This children’s book tells the true story of Roy and Silo, two male penguins at New York’s Central Park Zoo that built a nest together, took turns brooding an egg, and raised Tango, the female chick that hatched. Anne Frank’s Diary, which was another illustrated book was banned due to the coming of age of Anne Frank and her awareness of sexuality.

The little boy’s backpack contains the books, “To Kill a Mockingbird”, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”, and “Jacob’s New Dress”. Harper Lee’s novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, explores themes of racial injustice, prejudice, and the moral growth of a child as she witnesses the unfairness of the adult world. The reasons it has been banned include the novel's depiction of racism, the use of racial slurs and the presense of violence, including a rape allegation. Huckleberry Finn was banned primarily due to its use of racial slurs, and its depiction of slavery and racial prejudice. And finally, Jacob’s new Dress was called a “threat to family values”, which is a thinly veiled attack from homophobic bigots.

Conservative groups have long seen preceived harm to the social fabric and have taken actions to shape and control over what children learn in public schools, particularly around issues of race, gender, and sexuality. Shielding those readers from topics that may make them feel uncomfortable can prevent critical thinking and erases essential historical understanding.

Banning books by or about marginalized communities or those about historical realities (LGBTQ+, Black, Indigenous, immigrant, etc.) can erase identities and limit representation. At the core, banning books for trivial reasons tends to stifle empathy, curiosity, and democracy. A strong society allows ideas to be examined and discussed—not hidden or erased.

Racial Diversity

In the Civil Rights Era when Rockwell painting Ruby Bridges, interracial couples were not heard of and segregation of the races existed. In my showing interracial children holding hands, it is a coming together to normalize the idea of love and the innocence that children have. They don’t know anything other then that they are children. It is hate and bigotry that is taught.

Children absorb societal messages from a young age. Seeing interracial couples teaches them that the idea of love and partnership transcend racial boundaries.

These children are learning the bigotry and racial prejudice that existed and they are overcoming these challenges. Exposure to these realities not only broadens perspectives but lays the groundwork for a more just and accepting society.

Now on to that spray paint…

History Doesn’t Forget

If you look closely, what appears as spray paint is literally not paint. I used flour for a reason. What this symbolizes is that even though people may try to hide history or ban books, you can’t erase history. The truth is always there behind the facts. All it takes is someone to wash it away and the truth can be revealed.

Conservatives have often tried rewriting or obscuring history to maintain dominant narratives that serve their ideological goals. This can take the form of downplaying the horrors of slavery, sanitizing colonialism, or minimizing the role of systemic racism in shaping modern society. By pushing for bans on books, restricting how educators can discuss race and gender, or reframing historical events to portray them in a more favorable light, they attempt to erase uncomfortable truths and replace them with a more palatable, often mythologized version of the past. This deliberate manipulation or omission of facts not only distorts public understanding but also hinders progress by refusing to acknowledge the real roots of social and political injustice.

And now my painting, Whitewash, revealing one of America’s ugly truths. One that not only contains slavery but the systemic racsim that existed and still exists today. Conservatives have often attempted to whitewash history rather than confront the deep-rooted racism that this painting exposes. By downplaying the violence and resistance and ignoring or distorting facts, they seek to rewrite history in a way that erases the brutal realities of segregation and the courage of those who challenged it. But just like Rockwell, artists are here to remind the public of what exists.

Ruby Bridges walked forward with quiet courage, becoming a lasting symbol of resilience and hope. Her bravery helped pave the way for generations of children to receive an equal education, and today, The Problem We All Live With stands not only as a reminder of past injustice but as a tribute to the strength it takes to change the world—one small step at a time.